A lot of ink has been spilled of late about what causes mass protests, and what connects episodes of protest across different countries. Economic inequality, unemployment, corruption, middle-class rage, youth, social media…the lists go on.

Availability bias and selection bias are real problems in many of these on-the-fly analyses. Often, we see mass protests erupt in one country, search our minds for relevant examples, and then deduce the causes of those events from the things we notice they have in common. The set of potentially relevant examples is constrained by our memory, which is usually pretty limited. At the same time, the supposed relevance of those other examples is often affected by their emotional salience, which, in turn, is influenced by the amount and kind of news coverage they received. When we try to impose some structure on this thought process, we usually start with, and often don’t get past, geographic and temporal proximity. Equally important, we rarely stop to think about similar cases in which protests didn’t occur, a crucial step in causal inference.

I think we can get a better handle on why episodes of mass protest happen where and when they do—and how episodes in different countries are connected to each other—by taking a broader view from the start. We live in a global system. This means that large-scale political actions result from interactions between structural features and processes at the local and larger levels.

Local structural features don’t determine whether or not societies will experience specific types of political action, but they do shape a society’s propensity for them. Borrowing a phrase from John Miller and Scott Page (p. 96), these features “mediate agent interactions by constraining the flow of information and action.” In the case of mass protest, evidence indicates that number of relatively simple and obvious things have powerful effects on the likelihood that large numbers of people will take to the streets to make political demands. Among those things are population size, urbanization, and what political sociologists call the “political opportunity structure,” which is mostly but not entirely about the scope of civil liberties and state repression.

Notably absent from that short list are structural sources of grievance, like income inequality or corruption. I’ve left inequality off the list because I’ve seen and discussed evidence that its effects are weak (here). It’s harder to test the claim that corruption causes mass protest because we don’t have great cross-national time-series data on corruption, but my hunch is that it’s not especially powerful, either. Instead and like Fabio Rojas, I think participants and observers often select these issues as framing devices for protests that are already underway, but that doesn’t mean those issues actually caused the action in the first place.

Whatever the true set is, though, these structural features change slowly, and many societies exhibit many of them, yet mass protest is rare. So, to explain why protests happen, we need some more dynamic elements in our model. Based on empirical evidence, I see a few as especially important: economic downturns; austerity; inflation, especially for basics like food and fuel; and elections.

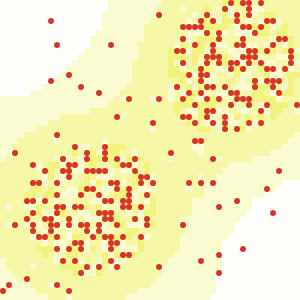

As we’ve seen in the past few years, these processes often have common underlying causes and are interconnected. Shifts in global oil markets can cause fuel prices to rise; rising fuel prices often drive food prices up; inflation can trigger recessions; recessions can compel governments to adopt austerity measures; frustrations over austerity can catalyze no-confidence votes that trigger early elections; elections can spur spending that produces inflation; and, crucially, swings in one market or one country’s economy can reverberate across many others. These interrelationships help to explain why mass protest seems to occur in waves, or episodes that cluster in time and space.

The systemic character of those common “triggers” isn’t the only thing that can connect mass protests across space and time, however. Contagion plays a role, too, and it comes in various forms. As Marc Beissinger observes, apparently successful protests can inspire imitators, a process he calls emulation. Protest may also spread through the deliberate efforts of interested parties, including but not limited to foreign governments and transnational activist organizations like Avaaz and the Open Society Foundations. (Just because dictators are often paranoid about “foreign agents” doesn’t mean someone isn’t really out to get them.)

All of the dynamic processes discussed so far are sources of positive feedback. They amplify earlier changes, pushing the system toward greater instability. Of course, would-be protesters aren’t the only ones imitating and teaching. As Beissinger observes and Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow also argue (see here), state officials, soldiers, police, and other counter-revolutionary forces also watch and talk to each other and adapt their tactics in response to the forms and patterns they see elsewhere. While economic reverberations and contagion produce positive feedback, adaptation by groups invested in the status quo produces negative feedback. What the former amplifies, the latter dampens. Coupled with structural sources of friction and inertia, these negative feedback loops help explain why mass protest doesn’t spiral into local and then global chaos.

New communications infrastructures and technologies aren’t triggering the protests we’re seeing, but they’re probably making them easier. Other things being equal, easier and broader communication creates larger networks with less friction. Governments and police also use and adapt to these technologies, however, so they aren’t always and automatically facilitators of collective action and sources of positive feedback for activism already underway.

Mass protest surely involves many causal mechanisms, at least some of which reside at the level of the (potential) participant. Importantly, though, those mechanisms need not be the same for everyone. One of the most important feature of human societies is their heterogeneity, and that heterogeneity means that there can be many different paths to choosing to participate or to stay home.

That said, one of the individual-level mechanisms that probably plays a role in many mass protests is loss aversion. As summarized in Tversky and Kahneman’s prospect theory, when making decisions in the face of risk, humans tend to think in terms of changes from the status quo instead of final states, and in their thinking about those changes, losses are weighted more heavily than gains. The resulting loss aversion helps explain why economic losses caused by recessions, austerity, and inflation can spur people to protest in ways that opportunities for economic gain rarely do. The threat of those losses has a psychological effect that is stronger than the prospect of similar gains and is not strictly determined by the likelihood of the ensuing protests’ success.

Risk-seeking behavior may be another important causal mechanism. While many individuals prefer to avoid risky situations, others seek them out (see here for relevant evidence). This is one place where the aforementioned heterogeneity plays an important role. Risk-embracing individuals are more likely to become the “early risers” whose daring actions change the information others have about their predicament, and thus their willingness to act out.

As Deborah Minkoff shows, the function early risers serve isn’t just informational. At a level in between individuals and the global system, early risers can also catalyze changes in the density of relevant organizations. These changes in organizational density, in turn, can help carve out a resource niche and create an infrastructure that allows protests to persist and expand over time. As the niche becomes increasingly crowded, however, barriers to entry rise, and the resulting feedback can tip from positive to negative. Along with the aforementioned Red Queen’s Race between protesters and police, this organizational ecology helps explain why mass protests eventually peter out, even in cases where relevant organizations survive and perhaps even continue to grow.

Finally, and I hope obviously, there is also a healthy dose of randomness in this system. We can recognize that mass protests unfold and interconnect in ways that exhibit patterns without believing that the system as a whole is deterministic.

Oral Hazard

/ July 5, 2013I suspect that contagion is a HUGE factor. Recent events in Brazil have made me wonder whether the “Arab Spring” phenomenon influenced Brazilians, who are certainly not muslim in any numbers. It seems that students/youth are typically the “patient zero” population for mass protests. The mechanism by which older adults are influenced to “defect” from non-protester state to protester state in solidarity with the nucleus that starts a protest is of interest. Also, the role of monkey-see-monkey-do conformity in local interactions around crowd formation. (Homer Simpson: “Look at that mob of angry chanting people. I think I should join them!”)

Grant

/ July 5, 2013It seems more likely to me that it’s simply that all nations are feeling the effect of global economic problems than real contagion (for lack of a better word) spreading from North Africa and the Middle East to South America. During the 1930s politics were very different between Europe and Asia, the economic upheaval still helped cause political unrest and violence even though the people responsible had different histories and often very different goals.

dartthrowingchimp

/ July 5, 2013Figuring out which of these views is closer to the truth is, I think, virtually impossible. It’s all so endogenous, and there’s no way to run a controlled experiment that would help clarify things. Simultaneously fascinating and frustrating.

Oral Hazard

/ July 8, 2013And definitions are so slippery. For example, FB and Twitter as “vectors” of contagion — or is it worth looking past the cliche to seriously consider that, for “Arab Spring”-type social activism on a mass scale, the “medium is the message” by embodying greater connectedness (and thus greater expectation of “democratic” voice)? Dunno. But in any case, I used the word “suspect” advisedly — to connote hypothesis rather than certainty.

alexhanna

/ July 5, 2013Nice post, Jay. A few thoughts.

On the topic of “prospect theory,” have you seen the David Snow et al. article on “quotidian disruption” (http://www.mobilization.sdsu.edu/articleabstracts/031snow.html)? The basic gist is that when the basic, taken-for-granted operation of life and standardized routines are interrupted or threatened then people engage in mass protest.

I think there’s a lot to be said about routine and non-routine forms of protest as well, and the importance in making the distinction in social movement mobilization. Mobilizing of Mothers Against Drunk Drivers is different from June 30 in Egypt is different from the Klan mobilization of the 1920s. Useem 1998 in Annual Review of Sociology (http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.215?journalCode=soc) goes into a little bit more in detail.

dartthrowingchimp

/ July 5, 2013Thanks, Alex. Your point about distinguishing routine from non-routine forms of protest is especially important, I think. I was lazy about defining terms in this post—what do I mean by “mass protest”?—and this rightly calls me on the carpet for that.

alexhanna

/ July 5, 2013It’s a distinction social movement scholars rarely make, one reason being that it’s hard to differentiate analytically between what qualifies as “routine” and “non-routine.” People just “know it when they see it.”

dartthrowingchimp

/ July 5, 2013I wish I’d remembered this article before I published the post, but on contagion, see also Kurt Weyland’s comparison of the so-called Arab Spring and the revolutions of 1848 and the role that optimism bias appears to have played in the spread of both:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1537592712002873

Max Abrahms and Karolina Lula see a similar process at work in the spread of terrorism as a form of rebellion:

http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/216/html

dartthrowingchimp

/ July 22, 2013Another one I would like to have cited in the original post: Cullen Hendrix and Idean Salehyan on evidence from sub-Saharan Africa that economic shocks are associated with higher rates of political conflict of various kinds, including protests, strikes, and riots:

http://jpr.sagepub.com/content/49/1/35.short

H/t to Patrick Brandt.