After publishing yesterday’s post on Freedom House’s latest Freedom in the World report (here), I thought some more about better ways to measure what I think Freedom House implies it’s measuring with its annual counts of country-level gains and declines. The problem with those counts is that they don’t account for the magnitude of the changes they represent. That’s like keeping track of how a poker player is doing by counting bets won and bets lost without regard to their value. If we want to assess the current state of the system and compare it earlier states, the size of those gains and declines matters, too.

With that in mind, my first idea was to sum the raw annual changes in countries’ “freedom” scores by year, where the freedom score is just the sum of those 7-point political rights and civil liberties indices. Let’s imagine a year in which three countries saw a 1-point decline in their freedom scores; one country saw a 1-point gain; and one country saw a 3-point gain. Using Freedom House’s measure, that would look like a bad year, with declines outnumbering gains 3 to 2. Using the sum of the raw changes, however, it would look like a good year, with a net change in freedom scores of +1.

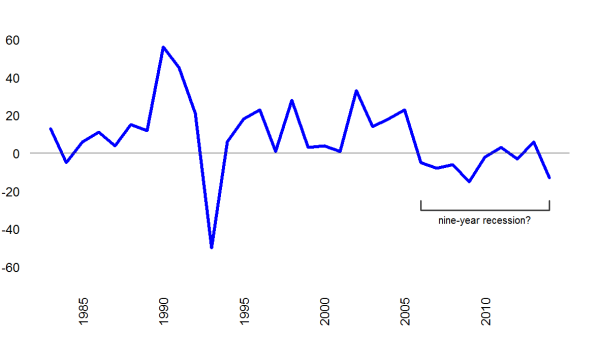

Okay, so here’s a plot of those sums of raw annual changes in freedom scores since 1982, when Freedom House rejiggered the timing of its survey.[1] I’ve marked the nine-year period that Freedom House calls out in its report as an unbroken run of bad news, with declines outnumbering gains every year since 2006. As the plot shows, when we account for the magnitude of those gains and losses, things don’t look so grim. In most of those nine years, losses did outweigh gains, but the net loss was rarely large, and two of the nine years actually saw net gains by this measure.

After I’d generated that plot, though, I worried that the sum of those raw annual changes still ignored another important dimension: population size. As I understand it, the big question Freedom House is trying to address with its annual report is: “How free is the world?” If we want to answer that question from a classical liberal perspective—and that’s where I think Freedom House is coming from—then individual people, not states, need to be our unit of observation.

Imagine a world with five countries where half the global population lives in one country and the other half is evenly divided between the other four. Now let’s imagine that the one really big country is maximally unfree while the other four countries are maximally free. If we compare scores (or changes in them) by country, things look great; 80 percent of the world is super-free! Meanwhile, though, half the world’s population lives under total dictatorship. An international relations theorist might care more about the distribution of states, but a liberal should care more about the distribution of people.

To take a look at things from this perspective, I decided to generate a scalar measure of freedom in the world system that sums country scores weighted by their share of the global population.[2] To make the result easier to interpret, I started by rescaling the country-level “freedom scores” from 14-2 to 0-10, with 10 indicating most free. A world in which all countries are fully free (according to Freedom House) would score a perfect 10 on this scale, and changes in large countries will move the index more than changes in small ones.

Okay, so here’s a plot of the results for the entire run of Freedom House’s data set, 1972–2014. (Again, 1981 is missing because that’s when Freedom House paused to align their reports with the calendar year.) Things look pretty different than they do when we count gains and declines or even sum raw changes by country, don’t they?

The first thing that jumped out at me were those sharp declines in the mid-1970s and again in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At first I thought I must have messed up the math, because everyone knows things got a lot better when Communism crumbled in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, right? It turns out, though, that those swings are driven by changes in China and India, which together account for approximately one-third of the global population. In 1989, after Tienanmen Square, China’s score dropped from a 6/6 (or 1.67 on my 10-point scalar version) to 7/7 (or 0). At the time, China contained nearly one-quarter of the world’s population, so that slump more than offsets the (often-modest) gains made in the countries touched by the so-called fourth wave of democratic transitions. In 1998, China inched back up to 7/6 (0.83), and the global measure moved with it. Meanwhile, India dropped from 2/3 (7.5) to 3/4 (5.8) in 1991, and then again from 3/4 to 4/4 (5.0) in 1993, but it bumped back up to 2/4 (6.67) in 1996 and then 2/3 (7.5) in 1998. The global gains and losses produced by the shifts in those two countries don’t fully align with the conventional narrative about trends in democratization in the past few decades, but I think they do provide a more accurate measure of overall freedom in the world if we care about people instead of states, as liberalism encourages us to do.

Of course, the other thing that caught my eye in that second chart was the more-or-less flat line for the past decade. When we consider the distribution of the world’s population across all those countries where Freedom House tallies gains and declines, it’s hard to find evidence of the extended democratic recession they and others describe. In fact, the only notable downturn in that whole run comes in 2014, when the global score dropped from 5.2 to 5.1. To my mind, that recent downturn marks a worrying development, but it’s harder to notice it when we’ve been hearing cries of “Wolf!” for the eight years before.

NOTES

[1] For the #Rstats crowd: I used the slide function in the package DataCombine to get one-year lags of those indices by country; then I created a new variable representing the difference between the annual score for the current and previous year; then I used ddply from the plyr package to create a data frame with the annual global sums of those differences. Script on GitHub here.

[2] Here, I used the WDI package to get country-year data on population size; used ddply to calculate world population by year; merged those global sums back into the country-year data; used those sums as the denominator in a new variable indicating a country’s share of the global population; and then used ddply again to get a table with the sum of the products of those population weights and the freedom scores. Again, script on GitHub here (same one as before).