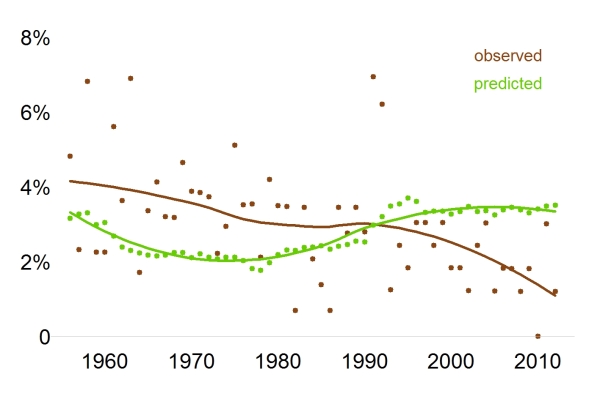

Here’s a plot of observed and “predicted” rates of political instability onset around the world from 1956 to 2012, the most recent year for which I now have data. The dots are the annual rates, and the lines are smoothing curves fitted from those annual rates using local regression (or loess).

- The observed rates come from the U.S. government-funded Political Instability Task Force (PITF), which identifies political instability through the occurrence of civil war, state collapse, contested state break-up, abrupt declines in democracy, or genocide or politicide. The observed rate is just the number of onsets that occurred that year divided by the number of countries in the world at the time.

- The “predicted” probabilities come from an approximation of a model the PITF developed to assess risks of instability onset in countries worldwide. That model includes measures of infant mortality, political regime type, state-led communal discrimination, armed conflict in nearby states, and geographic region. (See this 2010 journal article on which I was a co-author for more info.) In the plot, the “predicted” rate (green) is the sum of the predicted probabilities for the year divided by the number of countries with predicted probabilities that year. I put predicted in quotes because these are in-sample estimates and not actual forecasts.

Observed and Predicted Rates of Political Instability Onset Worldwide, 1956-2012

I see a couple of interesting things in that plot.

First, these data suggest that the anomaly we need to work harder to explain isn’t the present but the recent past. As the right-most third of the plot shows, the observed incidence of political instability was unusually low in the 1990s and 2000s. For the previous several decades, the average annual rate of instability onset was about 4 percent. Apart from some big spikes around decolonization and the end of the Cold War, the trend over time was pretty flat. Then came the past 20 years, when the annual rate has hovered around 2 percent, and the peaks have barely reached the Cold War–era average. In the context of the past half-century, then, any upticks we’ve seen in the past few years don’t seem so unusual. To answer the question in this post’s title, it looks like the world isn’t boiling over after all. Instead, it looks more like we’re returning to a state of affairs that was, until recently, normal.

Second, the differences between the observed and “predicted” rates suggest that the recent window of comparative stability can’t be explained by generic trends in the structural factors that best predict instability. If anything, the opposite is true. According to our structural model of instability risk, we should have seen an increase in the rate of these crises in the past 20 years, as more countries moved from dictatorial regimes to various transitional and hybrid forms of government. Instead, we saw the opposite. He or she who can explain why that’s so with a theory that accurately predicts where this trend is now headed deserves a…well, whatever prize political scientists would get if we had our own Fields Medal.

For the latest data on the political instability events PITF tracks, see the Center for Systemic Peace’s data page. For the data and code used to approximate the PITF’s global instability model, see this GitHub repository of mine.

William Church

/ February 23, 2014I think it is about how you see history. I tend to see things as a Period Called: The 100 Years War Ending Colonialism. Your chart might support this view. As colonialism and imperialism declines states start determining their own future. (however imperfect as in Zimbabwe) When there is interference instability rises. For example, the recent unrest in Ukraine can be seen as the final unraveling of Russian influence (colonialism?). Thailand is a very slow very slow burning unraveling of Western domination and the true election of local leaders. Look how quiet the Philippines is since they go rid of Western government governments. More and more countries are electing governments themselves without influence. Isn’t it interesting that the world has become stable at the same time as the decline of USA influence. Hmmm???? Leave all of this chart and data to you guys. Since I have lived in all these places that is my take.

Honesty Now (@philoTruth)

/ February 23, 2014That’s an erroneous take on thailand, something I know about. If you want to simplify it: its the well educated, whiter city folk verses the much more numerous and darker skinned uneducated farmers and country folk. Colonialism? Can’t see that in the way colonialism is understood. There is some racism, but mainly its corruption. It’s all Thai’s there (even if some are from china originally). They’ve never been occupied. They need honest leaders who will care for the country as a whole instead only the people on their side. Trouble is all of asia morality is wrapped up in family and local communities, their entire take on things is seen as corrupt because looking out for those close to you is drilled into them. Much of that comes because there is no social welfare. The elders depend on the family 100%. So you bet you’ll see families colluding, its survival for most of them, for the rich its just normal because everyone else does it.

William Church

/ February 24, 2014Thanks for the rebuttal and I accept most of it. However, I was more thinking about imperialism than colonialism. Like who supported the rich white city regime in the first place so that it would be stable so that a certain country could prosecute a war near by 40 years ago. That is why I said a very very very slow burn. Again, thanks for the comment and I think there might be space for both.

Grant

/ February 24, 2014Considering that Russia is geographically next door to Ukraine I don’t see how we can assume there will really be an end to Russian influence in Ukraine. I would think it more likely we’ll see more of the past, eras where one nation or group of nations to the west is influential and eras where a nation or group of nations to the east is influential.

Thailand has been more corruption, coups and counter-coups since the end of World War II, and I see very little to suggest that it’s going to change in the near future regardless of who holds power.

The Philippines are hardly what I would call quiet. Just because they aren’t in the middle of a massive civil war does not mean that they don’t have corruption and political violence, not to mention the border tensions in the South China Sea.

And if you’re blaming this on the United States and European governments, exactly how do you explain the serious economic problems of Venezuela and Argentina, the aggressiveness of China over borders, and the revolutions and civil wars in the Middle East, none of which can be explained under the assumption that the problems stemmed from the West* and shouldn’t be happening with Western nations less powerful than they were before. These aren’t still-lingering events from the past, these are new political events.

*And it is very strange to hear anyone talk about Russia as a western nation.

William Church

/ February 24, 2014Let me work backwards. Russia is historically part of Europe. It was only from a Cold War view that were not. I urge you to read history and relationship between the Czars and Europe and you will see that Russia was a vital player in Europe.

Philippines is more stable now than they ever have been. Peace treaty in the south, reasonable economic gain, and limited political unrest. I am open to proof otherwise.

I never blamed the current problems of Argentina and Venezuela on the US. They are internal problem; however, it is important to note that under Menem Argentina dollarized in an effort to get closer to US and that set off some of the current problems.

Middle East is misunderstood. The Arab Spring is about self determination and not democracy. The US and Europe without dispute have had a heavy hand in the region for decades. I would like to see evidence to the contrary.

Thailand I agree.

Ukraine. Obviously Russia is not going to just lay down and play dead. My point was that the current revolution shows the Western part of Ukraine wants to be oriented towards Europe and that supports my view that the Russian influence is decreasing.

Rich Stenberg

/ February 23, 2014I thought the last comment was intriguing, and although I’m not sure I agree completely, one could certainly point to some times and places, like Chile and Argentina in the 1970s, and much of Central America in the 1980s, where that point would have had some salience. I went to read the comments for this post, which usually I don’t, because I was thinking of pointing out something else that struck me–something perhaps close to what was already said. My reading of your post was to the effect of “there was a significant change in the trend lines for domestic crises and predicted domestic crises at the end of the Cold War, at which point the first fell greatly just as the second predicted a rise, inverting the model from over-predicting to under-predicting. I’m not sure why that is.” But, although you mentioned the end of the Cold War, I didn’t see it directly suggested that the end of the Cold War was part of the reason for this change. As suggested above, less colonialist behavior and meddling could well be the mechanism of that, although I can recall certain recent posts on this blog that implied the opposite. At the least, it seems that after 1990 the situation went from one in which important actors in the international community might occasionally have a stake in a country descending into instability and conflict (which Syria might currently be experiencing a flavor of?), at least if the alternative were that it fall under the sway of an enemy, but after, with exceptions (one just noted), all important outside actors were generally invested in some sort of stability.

Tom

/ February 25, 2014I agree. The cross-over seems to be the end of the Cold War. Shouldn’t be worth a Fields-Medal-equivalent to point out that civil conflict occurs within the context of international politics, and that the end of the Cold War—a dispute featuring two transnational political ideologies backed by superpowers—should have a significant effect on global civil conflict going forward.

Grant

/ February 24, 2014I could think of many possibilities of varying strength, and no doubt there are academics who will argue for every single one of them.

It could be the creation of the U.N. and a somewhat effective forum for nations to address issues.

It could be the fact that many of the major powers have nuclear weapons or could have them in a matter of months, making great power conflicts far more dangerous.

It could be that the U.S. has so much power that already unlikely actions like genocide can be too dangerous for many to risk, and that interstate wars would be even more dangerous for one of the belligerents who might face American soldiers.

It could be a general trend of economic growth in South American and African nations means that political violence decreases (creating chicken and egg problems I know).

And of course there are plenty of counterarguments.

The U.N. can be slow to move and forced to note the interests of powerful nations. Declassified documents have shown that nuclear war nearly broke out several times more than we thought.

The U.S. has been unwilling to intervene in issues like the Rwandan genocide or Ethiopia/Eritrean war in the past, raising questions about whether America could be expected to use its force under most circumstances.

Some of the bigger growing economics still have political violence unresolved or new violence breaking out, for example India and South Africa.

Even assuming we are in an era of relative peace, it could take us decades to figure out the why, if ever.

Honesty Now (@philoTruth)

/ February 24, 2014Perhaps it isn’t the subject of the article but indirectly it is: The usa isn’t returning to normal and since it’s the world leader (or was), the entire world is likely to become less stable. I mean, what about all the signs of the u.s. instability? It’s a mess, people mistrust gov, corps, churches, the media, dems and reps less than ever, it hasn’t been this unstable since the civil war. Sooooo, normal? gosh, i must be missing something. interesting data, worthwhile and commendable, but what about the elephant in the room? Perhaps its framing.

Richard Fazzone

/ February 24, 2014Why the “differences between the observed and ‘predicted’ rates … of comparative [political] stability… [and] where this trend is now headed”? My simple answer: Those who make the predictions –the political class –cannot acknowledge their increasing impotency; that the world is getting better (and more politically stable) http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/11/28/23-charts-to-be-thankful-for-this-thanksgiving/ while the power of the political class to impact that trend is in decline. http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-end-of-power-from-boardrooms-to-battlefields-and-churches-to-states-why-being-in-charge-isnt-what-it-used-by-moises-naim/2013/03/08/009f462c-7c56-11e2-9a75-dab0201670da_story.html